Imagine, upon waking one morning, you find yourself blind. Without vision. Deprived of the one sense you’ve learned to rely on the most. You stir, disorientated, straining to see through the darkness. For a moment you believe it to be midnight, but the darkness is impenetrable and even the streetlamps from beyond the window fail to emit their usual glow. You call for help, and hear your family rush in. You’re scared now. You can’t see but only hear them as they reach your side. A doctor is called. And then you are on the way to hospital, where you are subjected to a series of neurological assessments made all the more alien by your blindness.

Finally, after a week as an inpatient, the doctor comes to your bedside. She settles by your side, rustling her notes, clearly preparing you for difficult news.

‘Your tests are normal’ she says, ‘there is no physical cause for your vision loss’. You have been diagnosed with functional blindness. You have been told, essentially, that your blindness is all in your head.

Ask yourself, if faced with such a diagnosis, would you accept it? Could you accept it? This is the harsh reality that many patients suffer when diagnosed with a psychosomatic illness.

Psychosomatic disorders are characterised by physical manifestations of psychological distress. They are symptoms that are often highly disabling and distressing yet extend beyond what can be explained by any physical disease a patient suffers. Physical manifestations of psychological phenomena are common even in healthy individuals. Crying during a sad film, heart racing before an exam, blushing when you are embarrassed. These are all examples of your body adapting to your emotional state. However, in psychosomatic illness, these physical manifestations are highly disabling.

It is thought that psychosomatic disorders occur when emotional distress, following trauma, is too difficult to process. Physical symptoms are easier to understand, and may even be less painful than the psychological torment one would otherwise be subjected to. This shift in suffering occurs involuntarily and subconsciously. It is important to note that these patients do not fake their symptoms. They feel as real as ones caused by physical tissue damage. The difference lies in the origin of the symptoms and the subsequent treatment needed. Where an epileptic patient would receive drugs, or perhaps surgery to stop their seizures, a sufferer of psychosomatic seizures would be referred to a psychiatrist.

Psychosomatic symptoms often resemble their physical counterparts, but have some key differences. Whilst symptoms of physical origin are determined by the damage that cause them, psychosomatic symptoms are determined by what one expects those symptoms to look like. The body conjures disability which is consistent with one’s own experience of illness. A case study patient, referred to as Alice, was shown to develop psychosomatic symptoms upon entering remission for breast cancer. Her mother also suffered this disease and fared less well, eventually succumbing to the illness. Unlike her mother, Alice did not receive radiotherapy. However, she started to develop muscle weakness and paralysis in the arm, just as her mother did following this intervention. Her symptoms were the consequence of the trauma felt by losing her mother, and were modelled upon the memories of her mother’s condition.

Other physical symptoms, such as chronic pain, depend on the sufferer’s emotions. The way this pain is processed in the brain changes depending on emotional context, showing how the brain responds and adapts to cause and exacerbate symptoms of psychological origin. This begins to show how physical symptoms can occur due to psychological distress, and helps to contextualise what psychosomatic disorders are.

To start understanding why a patient suffers with psychosomatic illness, one must consider the patient’s vulnerability, trigger and gain. These three factors are responsible for causing and perpetuating these disabilities. Freud suggested that vulnerability to psychosomatic illness came from repressed trauma or the emotional toll of being oppressed. Indeed, many of his patients were women of ‘superior intellect’ who were unable to express themselves due to societal restriction of the time, and many others confessed while under hypnosis to suffering sexual assault in the past.

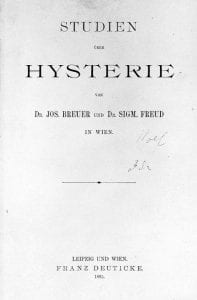

Figure 1: The front cover of Freud’s book: Studies into Hysteria.

Although many of Freud’s theories have been discredited, this basic concept remains broadly valid today. A history of sexual abuse is significantly more common in sufferers of psychosomatic illness than the general population. However, this only accounts for a third of sufferers. In other cases, more subtle examples of trauma may be responsible for psychosomatic illness. Furthermore, a case study patient, Jo, illustrates how oppression may increase risk of psychosomatic symptoms. Jo worked in a male dominated environment and found what she produced was unduly criticised. Forced to tears by a co-worker, she was thus called to her manager who told her this was inappropriate in the office. Shortly after, Jo suffered her first dissociative seizure. Jo was one of few patients who readily accepted her diagnosis of a psychosomatic illness. She saw a psychiatrist and recovered fully, later training as a physiotherapist. The outcome is worse in those who less readily accept the psychological origin of their illness. To many, the suggestion their symptoms are psychological in origin seems to reduce the integrity of their experience. This stigma serves as a major barrier for recovery in many psychosomatic patients.

Triggers are stressful or traumatic events which directly cause physical expression of psychological distress. Denial of stress is characteristic in these patients, so the trigger may be difficult to identify. A case study patient, Camilla, illustrates the elusive nature of these triggers. Camilla reported the start of her seizures after a relatively successful meeting. She reported a healthy family life and successful career. It was only with her husband’s correction that she recalled her first seizure actually occurred after the death of her young son. Although Camilla believed his death had been dealt with healthily, an intrusive thought about him resulted in highly disabling dissociative seizures over a decade afterwards. Patients’ memory and awareness of their own triggers are often buried within their minds. Camilla’s story shows the value of having loved ones to help recount the history of these symptoms.

Gain refers to what perpetuates the symptoms after their development. Although psychosomatic illnesses are not deliberate, they often serve to provide sufferers with benefits. These may appear negligible relative to disability caused by symptoms, but it is this gain which drives their continuation. A case study, Maria, demonstrates this well. Once a sufferer of childhood epilepsy, Maria now suffers chronic loneliness following the death of her parents. Maria has learning difficulties and struggles being alone. Missing her epilepsy medication resulted in a seizure and the attention this brings with it. Although Maria did not deliberately cause her subsequent seizures, she subconsciously recognised that these brought the company she so desperately yearned for. Upon recognising this, doctors implemented support for Maria which helped combat her loneliness. With this, her seizures faded over time.

Sufferers of psychosomatic disorders often react with hostility toward their diagnosis. These people are suffering with severe physical symptoms which often leave them disabled with their personal and professional lives thrown into disarray. Many feel as though the psychological nature of their illness somehow subtracts from its severity and diminishes the validity of their suffering. This is partly due to the stigma surrounding mental illness in comparison to physical illness. As such, it is important to encourage a societal change in attitude towards psychosomatic disorders. To do so, a better understanding of how these symptoms develop and express themselves is critical.

A biological approach may be able to provide some more insight into psychosomatic disorders. Historically, there has been a focus on outward behaviour but now, Functional MRI scans (fMRI) can be used to monitor brain activity during psychosomatic symptoms. Sufferers of sensory loss are shown to have reduced activation in the sensory parts of the cortex. Movement difficulties are associated with increased functional connectivity between the amygdala, an emotional centre, and the supplementary motor area, involved in initiating movement. Functional connectivity refers to how activity in one brain region influences activity in another, and this implies a connection through which one’s emotional state suppresses the generation of movement. However, these findings are only correlational. It is possible that this neural circuitry is what initially drives vulnerability to psychosomatic disorders, but it may also be the consequence of brain changes which occur following symptom onset.

The nature of psychosomatic illness is still foreign to patients and doctors. The idea that real and disabling physical symptoms can be psychological in origin is met with similar stigma to disorders like depression and anxiety. A common response reported to the diagnosis of psychosomatic illness is defensiveness; the belief one is being accused of faking the symptoms that have ruined one’s life. This highlights the importance of a changing opinion about these illnesses. As discussed, they are real and life changing. They can be cured with psychiatry, but only if the diagnosis is accepted. A societal change is necessary, to allow sufferers to feel secure in accepting their illness and the treatments available to them. Ultimately, psychiatry shouldn’t be seen as shameful but as a lifeline.

All case studies discussed in this article were described in the book ‘It’s All In Your Head’ by Suzanne O’Sullivan. O’Sullivan is a neurologist who works regularly with psychosomatic sufferers. ‘It’s All In Your Head’ won the Wellcome Book Prize in 2016.