There is something oddly captivating about superlatives. What is the biggest? The fastest? The cleverest? This article covers one in particular, the oldest.

As a benchmark, human life expectancy is on average 72 years as of 2016 (WHO). However, a French woman named Jeanne Calment has holds the record as the longest-lived human at 122. Humans live considerably longer than the majority of other animals, but even with access to medicine and healthcare, our records pale in comparison to other species.

Pictured: Adwaita (image source)

If you were to ask most people, “What is the longest living animal?”, the tortoise immediately springs to mind. Adwaita, a male Aldabra giant tortoise who died in 2006 had a reported age of 255 according to oldest.org, more than double anything humans have managed. Adwaita was one of many tortoises who surpassed our comparatively measly life expectancy, and was already a quarter of a century old before the USA came into existence.

Picture: Bowhead whale (image source)

Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) also make human lifespan look minuscule. These giant, gentle filter feeders reside in the icy waters of the Arctic ocean, spending much of their time under ice sheets. This means they are poorly understood. In 2007, Inuits caught a 50 tonne male off the coast of Alaska and found the remains of a bomb-lance (a 19th-century whaling weapon) embedded in the blubber, meaning this individual must have been around 120 years old. To uncover more data on the species, scientists used a technique known as aspartic acid racemization on 48 eyes donated by native Inuits. Results of the tests showed one individual, specimen 95WW5, was a staggering 211 years old. This makes bowhead whales the longest-lived mammal on Earth.

Pictured: Greenland shark (image source)

What about the longest-lived vertebrate? The bowhead whale held this record for a time, but another Arctic specialty, the Greenland shark, was recently found to have an even longer lifespan. Part of the sleeper shark family Somniosidae, named because of their lethargic movements, Greenland sharks are the slowest sharks on Earth with a cruising speed of a very safe 0.76 mph. They also may not reach maturity until they are 150. This relaxed lifestyle may contribute to their longevity, as studies using radiocarbon dating techniques put the oldest at a staggering 392 years old. Even more remarkable is the fact that the margin of error is 120 years, meaning at the least it was still 272 years old (60 years older than the bowhead whale mentioned earlier) and at the most 512 years old. To put that into perspective, its birth year (1504) would be the same year Michelangelo finished his sculpture David.

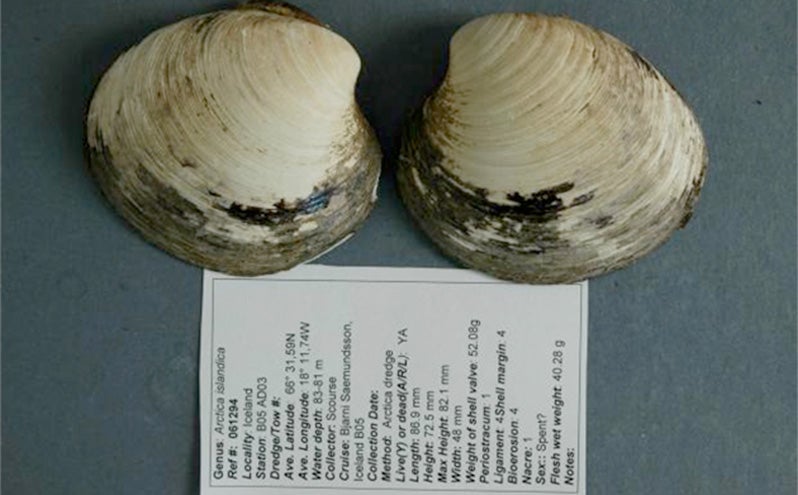

Pictured: ‘Ming’ (image source)

In 2006, 200 ocean quahogs (a species of clam) were taken as a sample for climate surveillance when a huge discovery was made. One of the clams, named ‘Ming’, turned out to be 507 years old. While the Greenland shark mentioned above could potentially have been older, scientists were very sure of Ming’s age due to the more reliable techniques they used, making it the most likely candidate as the oldest known animal. James Scourse, who led Bangor University’s research team responsible for Ming’s discovery, highlighted that Ming was merely one of 200 individuals. Given the total population of clams on Earth, the likelihood that Ming is the oldest is “infinitesimally small”.

Pictured: Immortal Jellyfish (image source)

An alternative winner of oldest animal, though, depending on how you judge these things, is the aptly named ‘immortal jellyfish’ (Turritopsis dohrnii). While most animals follow a linear life cycle of birth, followed by maturity and then death, immortal jellyfish can simply revert back to a polyp, a sessile, immature stage in their life where they remain attached to the seabed. When the need arises, the jellyfish can then go back to their free-swimming mature medusa stage, undergoing these changes as many times as needed. This means they are (quite literally) biologically immortal.

So what’s the secret? In the case of vertebrates, longevity is often attributed to their metabolism and the proteins that regulate it. As a general rule, larger vertebrates are better at managing their energy and as a result have slower metabolisms, which leads to a slower rate of cell division. Studies have found the number of times a cell can divide has a seemingly insurmountable limit, named the Hayflick limit. Once this number is reached, cells essentially commit suicide and the animal enters its final stages of life. Another factor in ageing is DNA repair from proteins. Animals that live longer tend to have advanced mutation pathways of these proteins, meaning these proteins change in form and function over time, and studying these could allow us to understand (and maybe even manipulate) our own ageing process. With much of this information on the frontier of what we know about the ageing process of animals, the conservation of long-lived species is paramount to continued research in this area.

As remarkable as all the animals listed here are, their resilience to time is of little defence against the dangers that humans pose. The tortoise, whale, and shark (along with many of their relatives) are all very sensitive to climate change and overhunting, which are pushing these animals to the brink of extinction. Should we be too careless in our actions, we may lose these species, and the incredible secrets they hold before we have a chance to properly understand them.