Weaving eye-catching optical illusions and strange case studies together with a passion for his subject, David Eagleman’s Incognito is both accessible and challenging to the average reader. The depths of the subconscious mind explored in this book address the age-old question: why do we do the things we do?

and strange case studies together with a passion for his subject, David Eagleman’s Incognito is both accessible and challenging to the average reader. The depths of the subconscious mind explored in this book address the age-old question: why do we do the things we do?

An assistant professor of Neuroscience at Stanford University, David Eagleman is a popular science writer and academic who’s known for writing engaging books on the subject. Incognito is a journey into the way the brain works but also touches on the morality, psychology and history behind the study of the most complex organ in the body.

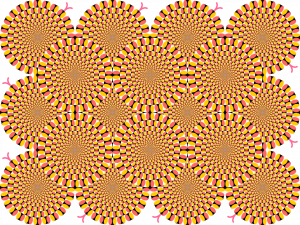

Beginning this book, it’s easy to feel at ease. Complimenting the reader’s appearance in the second sentence is one of the nicest first impressions an author can give. It is in these moments where Eagleman consistently excels, being informal without dumbing down the science and presenting the densely packed ideas of the subject in easy to digest segments. The optical illusions and diagrams used in this book are enthralling and serve a purpose, underlying the principles behind each of the chapters.

One of the themes of this book, consciousness, is approached in an unusual way. Instead of spending every page talking up this elusive enigma he puts the other brain processes front and centre, highlighting their importance and bringing intrigue into otherwise unremarkable areas. For me, cognition is the most alluring aspect of the brain and from reading the back cover I assumed this book would have nothing interesting to offer me. I was wrong.

A fascinating example of one of the many case studies in this book is that of Charles Whitman, who killed 13 people at the University of Texas in 1966. As Eagleman lays out the detail of the case it is easy to feel a sense of disgust at such a dreadful crime and paint Whitman as a completely evil individual, but Eagleman doesn’t do this. The author asks the reader to consider the autopsy of the killer, which revealed that a giant tumour pressing on Whitman’s amygdala could have been the source of the extreme outburst. A really interesting question is posed: do you blame the person or the tumour for its part in the tragedy. Had it not been there, would 13 people have lost their lives? Wading into this ethical quagmire, Eagleman confronts the entire prison system head-on in the final chapter, explaining the need for real justice based on rehabilitation and the level of modifiability in a prisoner’s behaviour.

If you are not from America or well versed in popular culture, this book can seem odd in places. You won’t be expected to know much science, and concepts will instead be better explained if you know who Mel Gibson is or if you’ve seen the film The Truman Show. He uses baseball to highlight how letting your unconscious mind take control can get you a home-run and how taking conscious control can hinder this process. Analogies are a fun approach, making it easier to engage with the material and take onboard the information. However, this book fails at some points to walk the line between the fun and the fascinating, at times being distractingly referential and humorous instead of letting the science speak for itself.

Altogether, I would say this book offers a great insight into the world of neuroscience; it is ambitious and covers a lot of ground, coming up with more questions than it answers. Although at times it can feel as if it has lost direction, a new idea will sneak up on you and you’ll learn something new. Whether you’ll start doing a sudoku a day to build your cognitive reserve or testing your visual receptors with the illusions inside, you will certainly take something valuable away from this book.