The German academic publisher Springer has recently brought out a whole book written by a piece of artificial intelligence software called Beta Writer. The book, Lithium-Ion Batteries: a machine generated summary of current research, can be downloaded free of charge as a PDF. Battery technology might not be a topic of interest to many readers of this blog – but could this be the start of a change to science writing in all fields?

The German academic publisher Springer has recently brought out a whole book written by a piece of artificial intelligence software called Beta Writer. The book, Lithium-Ion Batteries: a machine generated summary of current research, can be downloaded free of charge as a PDF. Battery technology might not be a topic of interest to many readers of this blog – but could this be the start of a change to science writing in all fields?

It’s certainly interesting. If I’m honest, what we have here is hardly a book at all – it’s more like the output of an automated abstract generator pulled together in book form. Frankly, this information would be far better presented as a web page. However, there’s no doubt that there is some interesting work going on here, particularly in the introduction and conclusion sections of the ‘book’.

The whole thing starts with a (human written) preface explaining the technology – by far the most readable part of the text. We then get four ‘chapters’ of machine-generated content, which each have the format introduction/ set of abstracts / conclusion. Obviously it’s the introduction and conclusion that provide the most interest.

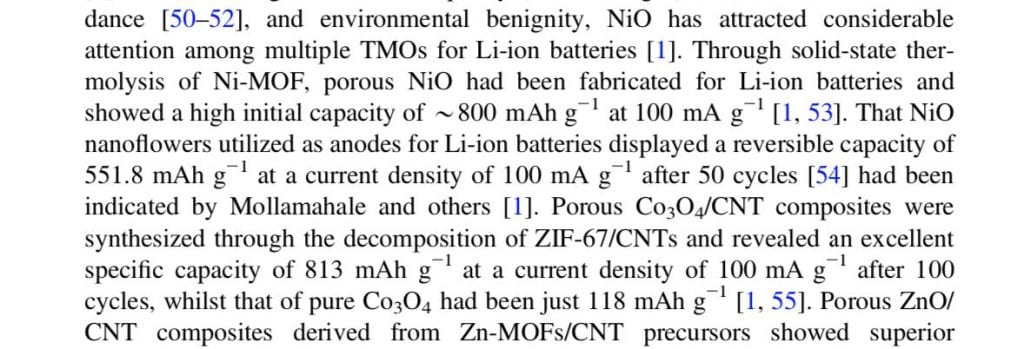

I’ll focus on the first introduction, though the same criticisms apply throughout. The first test of a piece of scientific writing is to take a step back and get an overview of a chunk of text – does it look like English or is it dominated by acronyms and numbers? A chunk out of the first page shows that this is very dense technical text, extremely low on readability:

The other two significant indicators of readability are whether the text is a collection of fact statements or is written using connectives and summary to give flow, and whether or not overall there is a structure that takes the reader by the hand and leads them through a communication process. On both tests, the book falls down in a big way. Pretty well every sentence is a standalone fact statement that could be a bullet point: there is no flow whatsoever. And although some attempt has been made to group these statements effectively, there is no sense of a thought-through structure. In the interminable-seeming introductions – the first one runs to 22 dense pages – there is no sense that we are going anywhere, just that we are experiencing randomly thrown together bits of data.

Inevitably, an automated process will produce some sentences that don’t quite work, so one essential here is to see whether these errors have been captured and fixed. A reasonably high percentage of the content does make grammatical sense, but there are regular hiccups – for example we get:

- ‘That sort of research’s principal aim…’ – it should be ‘principle’ not ‘principal’.

- ‘Materials, a number of metal oxides with high theoretical capacity have aroused more and more attention including…’ – that ‘Materials,’ at the start makes no sense.

- ‘Through Tang and others, mesoporous nanosheet is synthesized…’ – sounds painful for Tang et al.

- ‘It is still maintained the huge capacity of 611 mAg-1… when utilized as an anode.’ – doesn’t make any sense.

- ‘Apart from, few-layer nanosheets enhance a fast insertion…’ – apart from what?

- And so on for many, many more examples.

Going on comments I’ve had from some Springer authors, the level of uncaught or automatic-editing-generated errors is fairly high in their human-authored publications – these books tend not to be very well edited – but because they are starting with far more readable text, this is less of an issue.

So, should writers, whether producing academic or popular science be worried? Obviously, as a professional writer myself I’m biassed, but I would say ‘No’ – at least, not yet. The text in the introductions and conclusions is nowhere near the readability of a decent technical science book or paper, let alone the far higher writing quality required for a good popular science book. And the outcome also emphasises that even if, long-term, automated writing becomes more common, it is always likely to need a check over by a human editor to avoid errors creeping in. However, this is a fascinating experiment and Springer should be congratulated for getting this far.